Barcodes can be found in almost every business sector, from supermarkets and industrial warehouses to automotive manufacturing plants and construction. Barcodes didn’t just drop from the sky, though; considerable hard work went into their original development. Barcode history goes back to around 70 years ago when barcodes were initially designed and patented.

Barcodes can be found in almost every business sector, from supermarkets and industrial warehouses to automotive manufacturing plants and construction. Barcodes didn’t just drop from the sky, though; considerable hard work went into their original development. Barcode history goes back to around 70 years ago when barcodes were initially designed and patented.

The Barcode’s First Design

Barcode-like technology dates to 1934 in a patent by John Kermode, Douglass Young, and Harry Sparkes, working for the Westinghouse Electric Co LLC. Their patent described a system that utilized “photo-electric cells or other light-responsive means… following the marks on the cards or records” to sort cards and record data. Though this effort never quite took off, it would take long (approximately 15 years) for Bernard Silver and Joseph Woodland, both grad students at the Drexel Institute of Technology, to design the first actual barcode. A grocery store asked their institute to develop a method of automatically scanning product information. Silver and Woodland accepted and began designing a system of ink-based patterns that glowed when exposed to UV light. They had a partially worked system, but it was quickly abandoned due to the ink’s instability and high cost. Woodland kept working to develop an efficient method, relying on his stock market earnings as funding, living in his grandfather’s apartment, and resigning from his job as a teacher at Drexel.

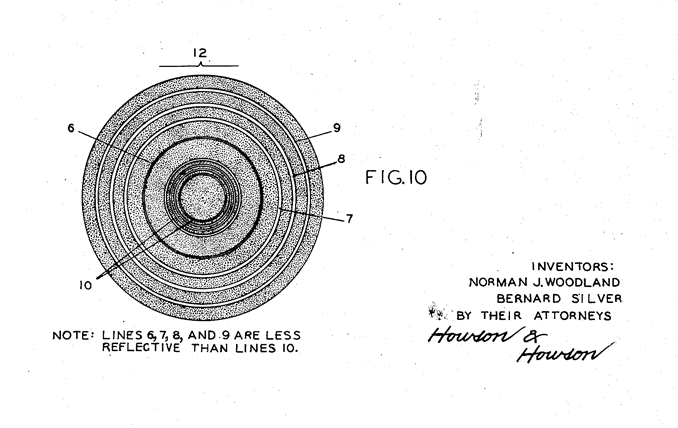

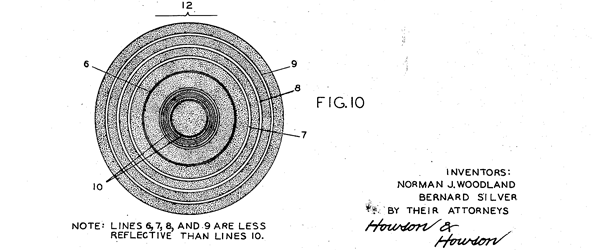

Eventually, Woodland filed his patent in 1949, which described the first-ever barcode. However, it has little in common with current UPC barcodes. It used concentric circles instead and looked like a bull’s eye. Using four white lines placed on a dark backing, Woodland patterned his invention off Morse code. Data was coded based on the presence or absence of the white lines, making it possible to categorize seven different types of products. By inserting more lines, you could increase the barcode’s ability to classify items (a code consisting of 10 lines could categorize 1023 different items).

In 1951, IBM hired Woodland, while his patent for the bull’s eye barcode was granted in 1952. IBM made an offer for the patent, offering a small amount of money because they thought Woodland’s invention lacked long-term sustainability; Woodland instead sold his design to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) at a higher price.

The Barcode’s First Appearance in the Industrial Sector

Interestingly, Woodland’s version of the barcode wasn’t the first tracking system used in industry, despite its status as the first to be patented. In the early 1960s, the railroad industry implemented KarTrak, a system designed by David Collins that worked on a series of 13 blue and red reflective lines of paint on steel surfaces. They had “stop” and “start” lines, with a 4-digit company identifier as well as a 6-digit railroad car number. As the cars were transported out of the yard, they would be scanned with this system. Regrettably, KarTrak was put out of use due to a severe economic downturn and because it was generally unreliable, with dirt preventing the barcodes from being read consistently.

UPC Barcodes Take Over Retail

So, what ended up happening with Woodland’s patented barcodes? In 1967, RCA attempted to use them at the Kroger Grocery store in Cincinnati but ultimately failed due to the barcode’s shape and large size, which took up too much room on each item, as well as the limited ability of the barcode to encode data. They also had a hard time printing them since minor imperfections made the barcodes unreadable. Ultimately, the system didn’t meet the needs of the grocery store and was pushed aside indefinitely. Around the same time, other businesses had decided that there should be a universal system put in place to standardize item tracking across the entire industry.

Though it didn’t work out, Woodland’s barcoding system gained a lot of media attention. This led to the creation of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Universal Product Identification Product Code and an offshoot, the Symbol Committee, to pick a universal code employed in all stores. IBM stayed committed to finding an efficient method of classifying items, hoping that the committee would accept its bid over Woodland’s model, which was still owned by RCA. IBM gave the project to George Laurer, who was the man responsible for the UPC barcoding system, which was designed based on stringent requirements of the committee. Laurer ended up with the rectangular, 10-digit UPC barcode that was accepted by the committee and is still used today. The very first item identified with Laurer’s UPC barcode was a pack of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum from Marsh’s supermarket in Troy, Ohio, with a facsimile of the same pack on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in honor of the game-changing nature of the barcode.

Today’s Barcodes

The popularity of barcodes rose steadily through the 1980s until 80% to 90% of the top 500 US-based companies were employing barcodes by 2004. They’re now an integral part of manufacturing, with companies like GS1, ISO, and even the military leading the way to standardize barcodes across the various industries that use them. With the global development of high-value sectors, including retail, automotive, aerospace, oil and gas, construction, and agriculture, barcodes are relied on more than ever to track and trace every single item efficiently.